The Effect of Military Spending, Female Representation in the Legislature, and History of Being a Colonizer on Feminist Foreign Policy Scores

Olivia Licata

While conventional approaches to foreign policy have historically dominated the international system, feminist foreign policy is arising as a progressive policy approach. Twelve states have officially adopted a feminist foreign policy: Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Mexico, Mongolia, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, and Spain (Foster and Markham). Although Sweden was the first country to formally adopt a feminist foreign policy in 2014, they abandoned it in 2022 due to the controversy that the label “feminist” generates (Walfridsson). Nevertheless, the feminist values enshrined in this foreign policy approach exist throughout the world. This unofficial and implicit reliance on feminist values reveals how some states are rethinking the ways in which they interact with the world through foreign policy.

This research seeks to discover what national characteristics make a state’s foreign policy more feminist. I hypothesize that low military spending, high female representation in the legislature, and a history of being a colonizer are correlated with high degrees of feminism in a state’s foreign policy. To test this hypothesis, I run a regression using the Feminist Foreign Policy Index. I control for the effects of liberal democracy and GDP per capita, and test for military expenditure, the number of women in the legislature, and the history of being a colonizer. Based on the results, I determine that female representation in the legislature is the only experimental variable that is statistically significant. Thus, this paper promotes gender quotas as a means to increase the number of women in the legislature, and make the state’s foreign policy more feminist. The results also reveal that higher liberal democracy scores are correlated with high feminist foreign policy scores. Thus, this paper recommends that state’s undertake policies that strengthen their democratic institutions to increase their liberal democracy score and make their foreign policy more feminist.

Literature Review:

Feminist foreign policy (FFP) is widely debated in both academic and policy spaces. Principally, there are debates on its definition. In general, FFP provides an “approach to promote gender equality and empowerment in external action” (UN Women 2022). While some FFP scholars focus primarily on the inclusion of women in systems and positions of power, others emphasize how feminist foreign policy challenges the entire patriarchal international system (Scheyer and Kumskova 2019). Because of its broad definition, FFP covers a range of issues relating to gender inequality within areas of defense, diplomacy, and international development (UN Women 2022).

Other scholars define feminist foreign policy more broadly, decentering the focus from gender. Lyric Thompson and Rachel Clement stress that FFP “prioritizes peace, gender equality and environmental integrity, enshrines the human rights of all, seeks to disrupt colonial, racist, patriarchal and male-dominated power structures” (Thompson and Clement 2019). Moreover, Jessica Cheung characterizes FFP as an “ethical policy” with core values of intersectionality, self-awareness relative to the needs of others, substantive representation and participation, accountability, and peace commitments (Cheung 2021). As such, feminist foreign policy is broadly defined by the values that constitute feminism such as equity, autonomy, peace, and freedom.

Despite the variable definitions, there is common agreement that feminist foreign policy is built on the understanding that “current principles of foreign policy are highly dependent on gender norms, roles, and structures, and that all institutions are inherently gendered” (Scheyer and Kumskova 2019). Joan Acker argues that while institutions are often referred to in gender neutral terms, in reality, they actually take on the “social characteristics of men” (Acker 1992). The understanding of institutions as gendered contributes to the assessment of many FFP scholars that existing systems must transform to address the gendered issues they impose.

Victoria Scheyer and Marina Kumskova identify five FFP indicators that are used to assess policy agendas. These indicators include political dialogue, safety and wellbeing, community empathy, inclusion and intersectionality, and gender analysis (Scheyer and Kumskova 2019). Based on these indicators, a foreign policy is more feminist when conflict resolution includes a gendered and class-based analysis of power, security comprehensively addresses concerns of intersectional groups, international communities are built on diverse interests, various types of actors are included in policymaking, and gender analysis is applied (Scheyer and Kumskova 2019).

Karin Aggestam, Annika Bergman Rosamond and Annica Kronsell argue that because conventional foreign policy is based on assumptions found in realism and liberalism (such as zero-sum competition, anarchy, and the inevitable rational pursuit of power), there are few opportunities for “ethical considerations or emancipatory messages such as feminism” (Aggestam et al. 2019). Eric Blanchard expands on the consequences of realism- and liberalism-based foreign policies, asserting that conceptions of masculinity such as the “citizen-warrior,” “rational economic man,” “breadwinner” and “civilian strategist” influence the characterization of states in the international system, and thus contribute to the gendered construction of the international system (Blanchard 2014). Conventional foreign policy often extrapolates traits stereotypically associated with men—such as warriorship, rationality, economic responsibility, and strategy—to the behavior of states. This approach narrows the scope of foreign policy by prioritizing state-level qualities over other dimensions of international relations. As Carver posits, “it is not that mainstream/malestream IR has prejudice against women’s (and children’s) lived experience in particular; rather, it has a prejudice against lived experience as such” (Carver 2004). By addressing this oversight, feminist foreign policy challenges these assumptions and introduces a more inclusive perspective, emphasizing human security and lived realities alongside traditional state concerns.

Theory:

This paper theorizes that higher feminist foreign policy scores will be correlated with lower military expenditure, higher levels of female representation in the legislature, and a history of being a colonizer. This theory is informed by the previous literature that asserts that traditional perceptions of security (those that focus primarily on the state and rely on the use of military force), low levels of female representation in positions of power, and dominating behavior in the international system are correlated with more conventionally masculine foreign policies. Moreover, this theory takes into account how both the explicitly gendered areas of policy – such as representation – and security policy areas – such as those related to militarism and imperialism – that can be influenced by feminist values are important considerations in assessing feminist foreign policy. This research aims to provide insight into the national characteristics that contribute to the degree of feminism in foreign policy.

Data and Methodology:

To test this theory, I built a dataset and ran a multiple regression. The dataset is composed of data on feminist foreign policy and five variables (GDP per capita, liberal democracy, military expenditure, women in the legislature, and history of being a colonizer) to represent different national characteristics. This dataset has 48 observations (for each of the 48 countries studied) from 2022. The multiple regression analysis reveals the relationship between each variable and feminist foreign policy.

To quantify feminist foreign policy, I use the Feminist Foreign Policy Index that was developed by Foteini Papagioti at the International Center for Research on Women. This index uses 27 indicators under seven priority areas: 1) peace and militarization (volume of arm exports, military expenditure, ratio of spending on health and education to military expenditure, support for normative disarmament frameworks, and the adoption of national action plan under the Women, Peace, and Security Agenda), 2) Official Development Assistance (ODA) (gender-equality focused ODA, ODA as the share of a country’s GNI, and funding for Code 15170: Women’s Rights Organizations, Movements, and Government Institutions), 3) migration for employment (migrant integration policies and the ratification of ILO Convention 97 on migration for employment and Convention 189 on domestic workers), 4) labor protections (ratification of ILO Convention 87 on freedom of association, Convention 98 on collective bargaining, and Convention 190 on violence and harassment in the world of work), 5) economic justice (financial secrecy enabling tax avoidance and illicit financial flows, investment dispute settlements, ratification of the OECD convention to prevent base erosion and profit shifting, enforcement of Buenos Aires Declaration on trade and women’s economic empowerment, and national action plans and enforcement mechanism on business and human rights), 6) institutional commitments to gender equality (percentage of women in ministerial level positions, seats held by women in national parliaments, and ratification of CEDAW without reservations), and 7) climate (carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP, the representation of women in party delegations in climate negotiations, contributions to the Green Climate Fund, net-zero pledges, and gender-sensitive Nationally Determined Contributions). The final FFP score is the mean of all the priority areas, each of which are the mean of their respective indicators. FFP scores are graded on a scale from 0 (least feminist) to 1 (most feminist). The average FFP score is .51, with both the median and mode being .52. The standard deviation is .13, which indicates that the average FFP score is within .13 points of the mean of .52.

To address the potential causal mechanisms, I control for the effects of two variables in the study. First, I control for GDP per capita. This data is from the World Bank. GDP per capita is measured in real dollars. The average GDP per capita across the 48 countries is $37,582, with a median of $28,277. The standard deviation is $29,298, which indicates that the average GDP per capita of the sample is $29,298 more or less than the mean. By controlling for GDP per capita, this research eliminates the possibility that the degree to which a state’s foreign policy is feminist is due to a disparity in economic resources.

Second, I control for liberal democracy. This data is from V-Dem. To determine this indicator, V-Dem uses the question: to what extent is the ideal of liberal democracy achieved? This measure takes into account the quality of democracy by the limits placed on government, and the level of electoral democracy. Liberal democracy scores are graded on a scale from 0 (least liberally democratic) to 1 (most liberally democratic). The average liberal democracy score is .68, with the median being .76 and the mode being .83. The standard deviation is .2, which indicates that the average liberal democracy score across all 48 countries is within .2 points of the mean of .68. By controlling for liberal democracy, this research accounts for the potential that regime type influences the degree to which a state’s foreign policy is feminist.

There are three national characteristics that I test to determine what contributes to the degree of feminism in a state’s foreign policy: military spending, the number of women in the legislature, and history of being a colonizer. To preface, both military expenditure and female representation in ministerial positions and national parliaments are included as indicators in the Feminist Foreign Policy Index. However, I believe it is important to test these indicators independently to determine whether they are independently correlated to the degree of feminism in foreign policy. In other words, this research aims to explore if low military expenditure and high representation of women in the government are correlated with the other 26 variables that comprise in the index, potentially revealing how they contribute to, rather than merely reflect, feminist foreign policies.

First, I test the effect of military expenditure on feminist foreign policy scores. This data is from the Military Expenditure Database at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute and is measured as a percentage of total government expenditure. The average military expenditure is 4.1% of total government expenditure, with the median being 3.24% and the mode being 3.04%. The standard deviation is 2.46, indicating that the average military expenditure is about 2.46 percentage points from the mean of 4.1%.

Second, I test the effect of women in the legislature on feminist foreign policy scores. This data is from the Inter-Parliamentary Union and is measured as a share of one. The average number of women in the legislature is .33, with the median being .33 and the mode being .4. The standard deviation is .11, which demonstrates that the average number of women in the legislature is .11 from the mean of .33.

Third, I test the effect of a state’s history of being a colonizer on feminist foreign policy scores. This data is from myriad sources (cited in bibliography). Because this is a binary variable (yes – the state was or is a colonizer vs. no – the state has never colonized), I created a dummy variable. If the state was or is a colonizer country, it is assigned a 1. If the state has never been a colonizer, it is assigned a 0. The average score is .43, with a median and a mode of 0. These measures indicate that there were more noncolonizer countries in the dataset than colonizer countries. The standard deviation is not relevant for this indicator because it is a dummy variable.

Results:

The results of this regression indicate that the number of women in the legislature is positively correlated with feminist foreign policy scores. The other two variables tested, military expenditure and history of being a colonizer, do not have statistically significant impacts on feminist foreign policy scores. It is notable that of the control variables, liberal democracy has a statistically significant effect on feminist foreign policy scores. GDP per capita has no effect.

Table 1

The summary statistics in Table 1 reveal how only liberal democracy and women in the legislature are statistically significant. A .01 point increase in the liberal democracy score is correlated with a .2101 point increase in FFP score. This is statistically significant at the .05 level, indicating that there is a 5% chance that this correlation is due to random chance. Additionally, a .01 point increase in the number of women in the legislature is associated with a .5412 point increase in FFP score. This is statistically significant at the .01 level, indicating that there is a 1% chance that this correlation is due to random chance.

Table 1 also shows that the residual standard error is low, at .09692, which reveals that the data fit the model relatively well. Moreover, the P-value of 2.334e-05 signifies that there is a low probability that the observed effect in the regression would have occurred coincidentally. Thus, the summary statistics demonstrate the strength of this model.

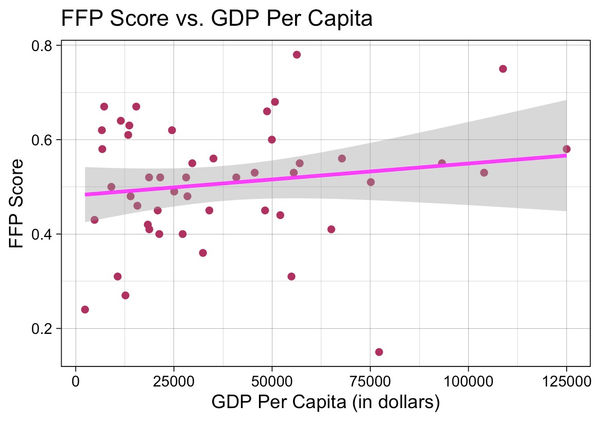

Figure 1

Figure 1 exhibits the relationship between FFP score and GDP per capita. While this relationship is not statistically significant, the graph reflects a slight upward trend as GDP per capita and FFP score increase. However, there is no evidence that this relationship is not due to random chance. Although the statistical insignificance of this variable is not important for the validity of the regression, it is interesting that there is no observable relationship between these two variables.

Figure 2

Figure 2 exhibits the relationship between FFP score and liberal democracy score. As Table 1 shows, this relationship is statistically significant at the .01 level. The upward trend demonstrates how an increase in liberal democracy is positively correlated with the degree to which a foreign policy is feminist. The statistical significance of this regression reinforces my decision to include liberal democracy as a control, as regime type is clearly correlated with FFP.

Figure 3

Figure 3 exhibits the relationship between FFP score and military expenditure. While this relationship is not statistically significant, the graph reflects a downward trend as military spending increases. However, there is no evidence that this relationship is not due to random chance. Unlike I predicted, there is no statistically significant correlation between these variables and the null hypothesis is accepted.

Figure 4

Figure 4 exhibits the relationship between FFP score and women in the legislature. As Table 1 shows, this relationship is statistically significant at the .05 level. The upward trend reflects that an increase in the number of women in the legislature is positively correlated with the degree of feminism in a foreign policy. The statistical significance of this regression reveals how important female representation in the legislature is to FFP.

Figure 5

Figure 5 exhibits the relationship between FFP score and history as a colonial power through a violin plot. The lack of statistical significance between these variables reflected in Table 1 is confirmed by the fact that the medians across the yes and no groups are practically the same. Furthermore, there is no evidence that this relationship is not due to random chance. Unlike I predicted, there is no statistically significant correlation between these variables and the null hypothesis is accepted.

Limitations:

There are a couple limitations to this research. First, the research has a small number of variables. Due to the scope of this project, I could only include two control variables and three experimental variables. While the results proved valid, the model could be improved by incorporating more controls and experimental variables in general. Not only would doing so improve the legitimacy of the results, but also could reveal more about what national characteristics influence the degree of feminism in a foreign policy.

Another limitation is that this regression only considers linear relationships. This model does not account for other types of potential relationships between variables, such as those that are nonlinear. If the model was adaptable to different types of relationships between variables, alternative results may have been revealed.

Finally, the understanding that statistically significant correlation doesn't equal causation is challenging for the military spending and women in legislature variable. While both variables were included in some capacity as an indicator in the Feminist Foreign Policy Index, this research attempted to test whether they were independently correlated with feminist foreign policy as a whole. However, this model made it difficult to see if this was in fact the case, despite the fact that women in the legislature was correlated with FFP and military expenditure was not.

Policy Implications:

The regression results indicate that making regimes more liberally democratic and increasing female representation in the legislature may lead to higher degrees of feminism embedded in a state’s foreign policy. These results can be used to shape policy that allows states to achieve this end.

First, states should work to ensure that their regimes are liberally democratic. As the regression reveals, this governance structure proves to be the most conducive to feminist foreign policies. To make the regime more liberally democratic, states should undertake policies that strengthen their democratic institutions. For example, states should enact policies that establish checks between different branches of government. Countries known to have strong political power distribution, such as Finland, Norway, and Sweden, also have the three highest feminist foreign policy scores (“10 Countries Seen to Have Well-Distributed Political Power”). This demonstrates how the balance of power within the government has implications on the liberal democraticness of the regime as a whole. States can also create policies that strengthen domestic civil society organizations. The aforementioned countries, as well as Chile and Germany, have high levels of civil society participation and score extremely high on the feminist foreign policy index (“Civil Society Participation Index”). This may indicate that civil society participation is relevant to the strength of liberal democracies. Finally, states can strengthen their liberal democracy by ensuring the validity of their elections. Finland, Sweden, Chile, Peru, and Germany have high perceptions of electoral integrity (“Elections”). They also have the highest feminist foreign policy scores in the dataset. Therefore, given that electoral integrity is an important component of liberal democracies, it could contribute to making foreign policy more feminist.

Second, states should aim to achieve gender parity in the legislature. This descriptive representation of women will lead to substantive representation, as reflected by the regression results. Through policies such as gender quotas, states can increase the number of women in their legislative bodies. Countries in the research sample with higher gender quota thresholds tend to have higher feminist foreign policy scores. These countries are primarily located in Latin America, as every country in the region (other than Suriname and Belize) have legislative gender quotas (either in the legislature as a whole or by political party nominations) (“Country Profiles”). For example, Peru, Chile, Mexico, Argentina, Colombia and Costa Rica have gender quotas ranging from 30%-50% (“Country Profiles”). They also are all within the top ten (of 48) feminist foreign policy scores in the dataset. Brazil was the only Latin American country in the dataset to be left out of the top ten feminist foreign policy scores. This may be due to Brazil’s struggle to achieve the threshold set by its gender quota, as only 18% of the legislature is women despite the quota being 30%. Thus, gender quotas may be an effective policy to increase the number of women in the legislature, therefore making the state’s foreign policy more feminist.

Conclusion

This model controlled for the effects of liberal democracy and GDP per capita in order to measure the relationship between feminist foreign policy and 1) military spending, 2) the number of women in the legislature, and 3) the state’s history of being a colonizer. According to the regression, a state’s score on the Feminist Foreign Policy Index is correlated with its liberal democracy rating and the number of women in its legislature. Based on these results, policymakers can make their state’s foreign policy more feminist by enacting policies that strengthen democratic institutions and increase female representation in the legislature.

Bibliography

“10 Countries Seen to Have Well-Distributed Political Power.” U.S. News & World Report, 30 Sept. 2019, https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/slideshows/10-countries-seen-to-have-well-distributed-political-power?onepage.

Acker, Joan. “From Sex Roles to Gendered Institutions.” Contemporary Sociology, vol. 21, no. 5, 1992, pp. 565–69. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2075528.

Aggestam, Karin, et al. “Theorising Feminist Foreign Policy.” International Relations, vol. 33, no. 1, Mar. 2019, pp. 23–39. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117818811892.

Blanchard, Eric. “Rethinking International Security: Masculinity in the World .” Brown Journal of World Affairs, vol. 21, no. 1, 2014, pp. 61–80.

Carver, Terrell. “II War of the Worlds/Invasion of the Body Snatchers.” International Affairs, vol. 80, no. 1, Jan. 2004, pp. 92–94. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2004.00369.x.

Cheung, Jessica. “Practicing Feminist Foreign Policy in the Everyday: A Toolkit.” Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 2021.

“Civil Society Participation Index.” Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/civil-society-participation-index. Accessed 9 Dec. 2024.

Clement, Rachel, and Lyric Thompson. “Is the Future of Foreign Policy Feminist.” Hall Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations, vol. 20, no. 2, 2019, pp. 76–94, https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/whith20&id=219&collection=journals&index=.

“Colonial Countries - an Overview .” ScienceDirect Topics, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/colonial-countries. Accessed 11 Dec. 2024.

“Country Profiles.” Gender Quota Portal, https://genderquota.org/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2024.

“Elections: A Global Ranking Rates US Weakest among Liberal Democracies.” The Electoral Integrity Project, 13 June 2022, https://www.electoralintegrityproject.com/eip-blog/2022/6/13/plxw8zwd4m7thgurqvyqdj6qjhyhjw.

“European Overseas Colonies by Colonizer.” Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/european-overseas-colonies-by-colonizer. Accessed 11 Dec. 2024.

Feminist Foreign Policies: An Introduction. UN Women, Sept. 2022, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/Brief-Feminist-foreign-policies-en_0.pdf.

Fisher, Max. “Map: European Colonialism Conquered Every Country in the World but These Five.” Vox, 24 June 2014, https://www.vox.com/2014/6/24/5835320/map-in-the-whole-world-only-these-five-countries-escaped-european.

Foster, Stephenie, and Susan Markham. “Why a Feminist Foreign Policy .” Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/blog/why-feminist-foreign-policy. Accessed 10 Dec. 2024.

GDP per Capita (Current US$). World Bank Group.

Liberal Democracy Index. V-Dem.

Monthly Ranking of Women in National Parliaments. IPU Parline, https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking/?date_month=12&date_year=2022.

Papagioti, Foteini. Feminist Foreign Policy Index: A Qualitative Evaluation of Feminist Commitments. International Center for Research on Women, 2023.

Scheyer, Victoria, and Marina Kumskova. “Feminist Foreign Policy: A Fine Line Between ‘Adding Women’ and Pursuing a Feminist Agenda.” Journal of International Affairs, vol. 72, no. 2, 2019, pp. 57–76. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26760832.

SIPRI Military Expenditure Database. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, https://milex.sipri.org/sipri.

Walfridsson, Hanna. “Sweden’s New Government Abandons Feminist Foreign Policy .” Human Rights Watch, 31 Oct. 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/10/31/swedens-new-government-abandons-feminist-foreign-policy.

“What Is Colonialism and How Did It Arise?” CFR Education from the Council on Foreign Relations, 14 Feb. 2023, https://education.cfr.org/learn/reading/what-colonialism-and-how-did-it-arise.

Zilla, Claudia. “Feminist Foreign Policy: Concepts, Core Components and Controversies.” SWP Comment, 2022. DOI.org (Datacite), https://doi.org/10.18449/2022C48.